ESSENTIALS OF SAFETY BLOG 9/14

We, our systems, our people, our procedures, our plant and equipment, our culture, and the way we all work are not perfect. Keep a weather eye out for trouble and steer away from it before it hits you, especially as you do any planning activities. It is always about getting the balance right: efficiency versus thoroughness; chronic unease versus lackadaisical carelessness; absolute confidence versus wariness of the effectiveness of controls. Getting the balance right requires leadership, conversation, and having time to think (blue work).

This is the ninth of a dozen or so blogs covering the Essentials of Safety that I talked about in the first blog of this series. We have covered an introduction – which we called Essentials of Safety, Understands their ‘Why’, Chooses and displays their attitude, Adopts a growth mindset – including a learning mindset, Has a high level of understanding and curiosity about how work is actually done, Understands their own and others’ expectations, Understands the Limitations and use of Situational Awareness and Listens Generously.

The other blogs in the series are:

- Controls risk.

- Applies a non-directive coaching style to interactions.

- Has a resilient performance approach to systems development.

- Adopts an authentic leadership approach when leading others.

- Bonus – The oscillations of safety in modern, complex workplaces.

Plans Work Using Risk Intelligence

As I mentioned in the introduction, I am using the term Risk Intelligence in a broad sense rather than the tight definition of experts like Dylan Evans. Essentials of Safety attempts to encapsulate some of the concepts and ideas of the Efficiency-Thoroughness Trade-Off (ETTO), Risk Intelligence itself, and having a suitable wariness for the effectiveness of controls and chronic unease. Task planning is such an important part of the creation of safe work. It is important not only with respect to the high-level long-term and short-term planning that a planning function may do but also for the day-to-day, and especially the task- by-task, planning that individuals attend to all day every day.

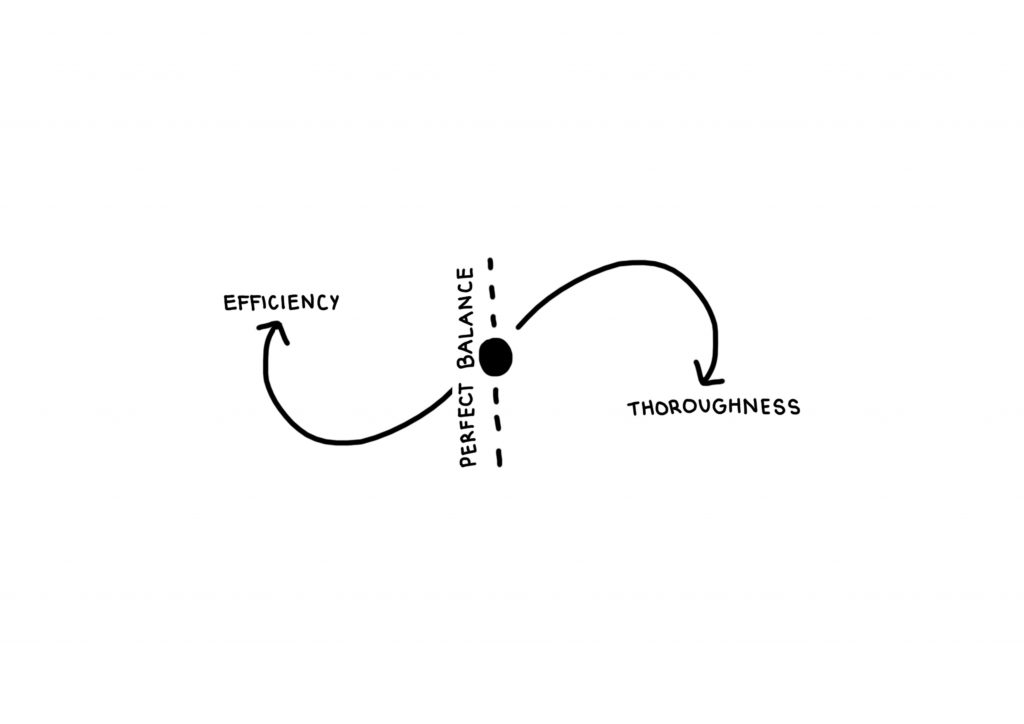

Fundamental to people being capable of doing the low-level task-by-task planning is an understanding that we cannot do everything perfectly, all the time. If we want everything to be perfect every time, then we are probably going to be very inefficient doing the task. I could spend three days cleaning my car, for example, but that is probably not the best use of my time. There is always a trade-off between efficiency and thoroughness in the tasks we undertake, and task planning needs to take this into consideration. Hollnagel calls this trade- off the ETTO principle. You cannot achieve excellence in both efficiency and thoroughness at the same time. It is not possible. There is always a balance. We can help people understand the ETTO principle by getting them to talk about when and how they apply the ETTO principle in their daily lives outside of work. We can then talk about how it is being applied as they attack their daily work-related activities. Once you think about it a bit, we all ETTO all the time.

Imagine doing your Christmas shopping. You could create an active spread- sheet, including the people you plan to give presents to, the options for presents for each recipient, and then a series of columns with the various providers of said gifts sorted automatically by quality, availability, and price. Once this is done, you could apply an algorithm that balances these variables with an overall maximum budget spend for the year. This is well on the ‘thorough’ side of the ETTO. On the ‘efficiency’ side, however, you could create a simple list of names and present ideas, nip into your local shopping centre, wander around for a few hours, and grab whatever you see that fits the bill. It’s more efficient, but you could also blow your budget or end up with sub-quality items. It is always a balance. This is the ETTO principle at work (Figure 1).

It is the balance of ‘time to think’ and ‘time to do’, or in the words, of Marquet ‘blue work’ and ‘red work’, that is at the heart of ETTOing. Helping people get that right is something that you need to push strongly. This is also a reminder that one of our tasks as leaders is not only to help people understand how to do their jobs but to arm them with the skills they need to do things that surround their jobs, like planning, handling uncertainty, managing adaptive problems, etc.

You can also talk about ETTO when we are in the field as leaders having field leadership conversations. We should have in our minds, as we have these conversations, that ETTOing can be a common driver of procedural shortcuts and procedural drift – heading towards efficiency compared to thoroughness in the application of the procedure to do the work.

You could talk with your people about the fact that due to ETTO, and just generally because we are all human beings, we will not get it right all the time. People need to expect failure and then to see what they can do to learn from it. Seeing failure as a learning experience rather than as a deflating experience is certainly the better attitude to have.

We all need to expect failure in ourselves. We also need to expect failure in the tools and equipment we are using. We all need to expect failure in everyone around us, including our leaders. They are, after all, human beings just like the rest of us.

Having an appropriate level of chronic unease also fits in with task planning and this expectation of failure nicely as well. That entails always having a level of alertness about what could go wrong. Having the mentality that everything going along swimmingly cannot last. Encourage people to try to keep an eye on things and have a back-up plan if things go south – i.e. anticipating a failure and already knowing what they are going to do to handle it.

If there is one guarantee in the world of safety and work, it is that people will fail. If someone goes up onto a scaffold with tools and equipment, they will drop some of them at some point in time. This is why we put up drop zones around scaffolding that is being worked on. Things will go wrong. When we drive our cars around, we need to be very aware of what others are doing. We know that other drivers, just like all of us, will sometimes get it wrong. We need to always look in the mirrors, down the side roads we pass, at the traffic lights, at what pedestrians and cyclists are doing, always planning to ourselves; what we will do if …

The identification of hazards is a pretty critical step to understanding the situation in which we find ourselves as we perform a task at work. The identification of these hazards is not something, however, that we do once at the start of a task. It is a process that continues all the way through an activity. The work of planning to control risks never goes away. In order to plan for how to do a task, people need to develop risk awareness, and then maintain it throughout the task.

Developing risk awareness requires work. Over time and with practice, operators can achieve a high-level awareness of risk – a sense of what is going on around them and if anything dangerous is developing. I am reminded here of James Reason’s idea of error awareness and chronic unease as well as Dylan Evans’s concept of Risk Intelligence.

We can help our people develop the much-needed risk awareness we require. Allow them to spend enough time understanding their equipment and systems – looking at vulnerabilities, understanding risk profiles and critical controls as they plan the task – and then give them sufficient time and skills to monitor any changes and/or drift during the task itself, so they are always being mindful during the work. The usual suspects of situational awareness, mindfulness, skilful observations, and mental models come up again for us during task planning.

We need to touch on Risk Intelligence here also as it is all about our ability to estimate risk probabilities accurately. We all know that we are not good at estimating risk and we are also not very good as individuals in understanding the limits of our own knowledge. This is what Risk Intelligence is all about. We tend to jump to answers in order to look good or to say what the easy answer is. We should rather think about what we know about the issue, whether those bits of information make the event more or less likely, and by how much it impacts the risk. Then we should check whether this hunch makes sense and how strongly it is being impacted by availability bias. Only then should we make an estimate of the probability of something going right, or the prob- ability of something going wrong. There are a number of methods to teach Risk Intelligence, including asking Fermi questions – questions that drive an improvement in estimating skills. This is useful when thinking about moving unknowns-knowns into known-knowns.

I am reminded of the Donald Rumsfeld stuff here:

There are known knowns; there are things we know that we know. There are known unknowns; that is to say, there are things that we now know we don’t know. But there are also unknown unknowns; there are things we do not know we don’t know.

A classic example of a Fermi question that I have used is asking a group how many piano tuners there are in the local state or provincial capital. Normally, there is nobody in the group who has the exact answer but through some lateral thinking they can all get a pretty good estimate, especially when averaged. To do this, they can generally recall an estimate of the population. Then think about what percentage may own tuneable pianos. They then assume that one piano tuner, working five days a week and taking half a day to tune one piano, can easily estimate how many piano tuners there are. A quick review of the internet can get you the answer of course but that is cheating. Doing this helps the individuals get better at problem solving and improves their Risk Intelligence. The trick is to help them realise that by using the knowledge that they already possess, they can solve problems that at first glance seem intractable. We have found that this skill is very handy when attempting to understand the risks associated with complex tasks during task assignments.

Risk intelligent people have an ability to access bits of information some- where in the backblocks of their minds that may be relevant, even if at first glance it does not seem obviously related to the problem at hand. It is true that many people cannot recognise the gaps in their own knowledge. They do not know what they do not know and they do not know that they do not know what they do not know – often they think they do know when they, in fact, do not know. I think I got that right.

Just like in all fields of endeavour, when we are trying to understand the level of situational awareness required for a task, it is unreasonable for a system to attempt to demand efficiency and thoroughness in the same breath. To help, we can build the systems that take this into consideration and hence do not put too many demands on the human to be aware of everything, all of the time. The way this can be done is to apply an ETTO filter to system development and changes. Try to make the system thorough enough such that the business is confident that the necessary and sufficient conditions will be created so that the system will deliver its objective. At the same time, we want to aim for the level of efficiency such that the system does not drive unnecessary resource use or requires people to have an unachievable level of situational awareness.

Most businesses are not High Reliability Organisations (HROs). Some do their utmost to progress in that direction and unfortunately only a few are crystal clear that a High Reliability Organisation is a journey and not a destination.

The standout area of focus for many on this journey is related to a preoccupation with failure and managing the unexpected.

When things are going well, laders should worry. When things are not going so well, leaders should worry. Leaders need not be obsessed with what could go wrong; they just need to be preoccupied with it. This preoccupation with failure is sometimes called chronic unease.

We need to remember that having a good run with safety in the past bears absolutely no relationship to what may happen today or tomorrow. The absence of a failure, incident, or injury means only that there has not been a failure, incident, or injury – it does not denote anything else.

I first read about chronic unease in James Reason’s books and loved the idea – as long as it is not taken to extremes, which some leaders have done in the past. Chronic unease is all about a healthy scepticism about whether stuff is going to be okay or not. I have heard the phrase ‘wariness of risk controls’ and ‘vigilance’ popping up in references about chronic unease and I recall a discussion in one of Reason’s books about ‘feral vigilance’ used by the then Western Mining Corporation (now BHP), which also points to a constant lookout for what could go wrong implied by chronic unease. So, what does the behaviour or action of a leader look like if they possess chronic unease and how does that affect safety?

Leaders can show chronic unease by asking questions in order to encourage their teams to question the way they work. Leaders can encourage their teams to question the accuracy of the procedures they are expected to use. They can ask questions in order to encourage their teams to challenge any normalisation of deviance and drift. They can ask questions in order to understand for themselves what is driving any differences between Work-As-Done, Work-As- Normal, and Work-As-Written.

In keeping with the concept of wariness of risk control or chronic unease, one of the ways we can ensure we maintain a preoccupation with failure is that we can take on a systems perspective that tells us we must look beyond the individual mistake or ‘error’ and understand the underlying structures, culture, leadership, and system interrelationships that create the required conditions for a failure, incident, or injury to emerge. We should encourage people to have sufficient unease such that they approach each day as if something will go wrong and then plan for it.

When in the field, we should always ask questions such as what is going on here that is different?; why do you think it is different this time?; what can we do about it, to manage it?; and have we normalised the difference as we have seen it before without any adverse outcomes?

As a leadership team as well as individuals in the workplace, we need to track small failures and weak signals. Differentiating between noise and signal is most assuredly not an easy thing to do. It is our role as leaders to supply the ongoing effort needed to see the signals and help drive the application of adaptive efforts in order for things to go right as well as to stave off catastrophe. We need to keep a very close eye on attempts to simplify processes to make sure we are not over- simplifying things, and to keep a close eye on the moving locations of expertise. Simplicity can hide unwanted, unanticipated, unacceptable actions and activities, which could increase the likelihood of an adverse outcome. It is much easier to identify large signals such as changes. Be wary of these also. We should view change – in just about anything from the legislative environment, legislator’s focus, technology and economic swings and roundabouts, production pressures, through to changes in equipment, tools, people, or level of complexity – as something that needs to be extremely well understood and managed.

Simply put, we should strive to ensure our systems result in HRO-style behaviours by our leaders. One example of this is with one of the system elements that can drive lead team routines mentioned earlier in the chapter. When you review or modify procedures for accuracy and then approve them, the system can drive you to always ask a few simple questions:

- Does the procedure (still) include mechanisms to make sure the job goes right?

- Has it simplified beyond clarity or sense?

- Has the review had effective involvement of the end user along with suitable expertise?

Another is in audit processes. When you are internally or externally audited, request the auditors ask a selection of leaders and frontline workers about how they believe the systems being audited aid progress towards an HRO-style operation. Welcome audits of your systems as they are methods that you can use to check yourselves and make sure you have not got too much complexity, too much complicatedness, or too much simplicity.

An Example

A client recently told me a story about a process they used in an attempt to simplify their workplace procedures and the planning that went into it. This project was not only aimed at increasing the level of simplicity but also about a serious reduction in the number of procedures and systems they had in their business. She told me that they were initially worried that the reduction in number and

complexity of procedures could result in a lack of direction and an increased risk of incidents and injuries. She was also worried that they would get it wrong with respect to eliminating important bits and leaving requirements in the procedures and systems that were simply clutter. When I asked how she managed all of these diverse needs, she explained that they took a long time to get the planning right and were driven by trying to get the ETTO balance right as they approached the problem. They also tried to take the advice of Jim Wetherbee out of his book Controlling Risk. He talks about asking two questions: as leaders in the business, they asked themselves whether the system change they were planning left the system, along with all its procedures accurate or not. They also asked whether those that needed to use the procedures also felt that the changed procedures were accurate. Wetherbee goes on to explain what accurate means: ‘Accurate includes being effective and representative of the organisation’s colle tive wisdom (including the end-users) on the best way to accomplish the task’. The client went on to explain that applying this filter to decisions and changes resulted in getting the balance right between efficiency and thoroughness and ending up with what they felt was a balanced system. Was it perfect? Absolutely not. But it was a great deal better than before.

Key Takeaway: We, our systems, our people, our procedures, our plant and equipment, our culture, and the way we all work are not perfect. Keep a weather eye out for trouble and steer away from it before it hits you, especially as you do any planning activities. It is always about getting the balance right: efficiency versus thoroughness; chronic unease versus lackadaisical carelessness; absolute confidence versus wariness of the effectiveness of controls. Getting the balance right requires leadership, conversation, and having time to think (blue work).