ESSENTIALS OF SAFETY BLOG 5/14

To get better at ‘safety’ you need to deeply understand how real work is undertaken, rather than just how you think it is being undertaken.

This is the fifth of a dozen or so blogs covering the Essentials of Safety that I talked about in the first blog of this series. We have covered an introduction – which we called Essentials of Safety, Understands their ‘Why’, Chooses and displays their attitude and Adopts a growth mindset – including a learning mindset.

The other blogs in the series are:

- Understands their own and others’ expectations.

- Understands the limitations and use of situational awareness.

- Listens generously.

- Plans work using risk intelligence.

- Controls risk.

- Applies a non-directive coaching style to interactions.

- Has a resilient performance approach to systems development.

- Adopts an authentic leadership approach when leading others.

- Bonus – The oscillations of safety in modern, complex workplaces.

Has a High Level of Understanding and Curiosity about How Work Is Actually Done

Eric Hollnagel reminds us that as managers, we need to understand that the way work is done out there in the real world is often not exactly the same as the way we imagine it is being done. If you have read Simplicity in Safety Investigations, you will have seen how I adapted the idea of Hollnagel’s Work-As-Done and Work-As-Imagined to talk about needing to understand how work is done (Work-As-Done), how everyone else does the work (Work- As-Normal), and how the written procedure or other documentation tell us how to do the work (Work-As-Intended) as a precursor to understanding the differences and hence the contributors to an incident. In hindsight, and in response to clients’ comments and suggestions, changing Work-As-Intended to Work-As-Written seems to strike a better chord with users of the investigation approach so I will use that terminology in this work. I read a very interesting tweet from Stephen Shorrock recently that talked about the large number of Work-As- … that are used today. The graphic in the tweet (from humanisticsystems.com) showed many:

- Work-As-Imagined.

- Work-As-Prescribed.

- Work-As-Disclosed.

- Work-As-Analysed.

- Work-As-Observed.

- Work-As-Simulated.

- Work-As-Instructed.

- Work-As-Measured.

- Work-As-Judged.

And, of course, here are the ones I have used:

- Work-As-Intended.

- Work-As-Normal.

- Work-As-Written.

This really shows us that we can talk about work through a wondrous array of lenses. I have simply chosen the three that seem to work for me here. Viewing work through many of these lenses can at times help us understand the workplace from differing perspectives and that can be extremely useful, especially when trying to understand what went wrong in a workplace incident and what we can learn from it. The three that I am focussing on are Work-As-Written, Work-As-Done, and Work-As-Normal.

Work-As-Written (WAW) represents that vast amount of detailed information contained in all of the procedures, work instructions, work orders, rules, commandments, checklists, injury prevention principles, Task-Based Risk Assessments (such as Task Hazard Analyses, Job Step Analyses, Job Safety & Environmental Analyses, etc.), and many other such instructional documents that drive work. Work-As-Written is often a complex and intertwined set of requirements.

Work-As-Normal (WAN) represents how those involved in doing work in the business normally do the tasks-of-interest that we are focussing on in the conversation or learning study. Details of Work-As-Normal are usually obtained through conversations with those who do the task-of-interest on a daily basis. We always use adverbs such as ‘normally’ or ‘it is common practice to …’ when talking about Work-As-Normal.

Work-As-Done (WAD) represents how the work is actually done at the time in question. This could be when a leader is out having a field leadership conversation, or it could be about activities leading up to a workplace incident being investigated. One thing to keep an eye on when exploring Work-As-Done, whether part of an investigation or as a part of day-to-day leadership, is the concept of drift. Practical drift is when the way the work is being done today has changed over time. This occurs frequently, especially when we have people teaching each other how to do the work. People pick up ways of working that may be easier or quicker and over time that way of working becomes the way we work around here (Work-As-Normal). Drift can also appear as procedural drift in Work-As-Written documents where we have tweaked procedures over time due to periodic reviews or changes after workplace incidents. This can sometimes be to the detriment of the level of control we have over the risks. We can end up with a procedure that misses the mark on critical controls and actually adds risk to a task.

Work-As-Written can sometimes get a bit out of hand in terms of its volume, complicatedness, and complexity, and it is worth spending some time on these aspects of the term. I was at a client’s operational site late in 2019 and was told that the business had over 20,000 documents in their system. Sorry, but this is absolutely crazy and unworkable. No human is capable of getting and keeping their heads around such a high number of system documents, procedures, etc. Work-As-Written can get complex and it can get complicated. We recognise that complexity, or more specifically an increase in the level of complexity, through changes, planned or otherwise, can encourage the creation of more complexity and increased risk of things going wrong – not as planned. This will often manifest as a misalignment between Work-As-Done and Work-As- Written. Complexity in systems and procedures can leave end users of those systems bewildered as to what to do. This can result in both Work-As-Done and Work-As-Normal being different from and inconsistent with Work-As-Written.

Complexity and safety are beyond adversaries and are causatively related. Complexity is inversely proportional to safety. I am not sure if some inverse square law applies here, but certainly when complexity goes up, safety has a propensity to go down.

A quick reminder on complex versus complicated. Rocket science is simple when compared to getting safety right. Rocket science is complicated and difficult to master, but not complex. In a complex modern workplace, it is not pos- sible to create a system that will cover all workplace scenarios. It is, on the other hand, possible to build a system that will get a man to the moon and return him safely to the Earth. The science is tough, especially orbital mechanics, but it is defined and structured. This is why we constantly seek to build resilience practices and adaptive skills in our people as these are essential for humans to operate in a complex environment.

One remedy for both complexity and complicatedness is simplicity and the simplification of Work-As-Written. We need to always look at work simplification with a complexity lens. Understanding that simplifying an operation can often improve reliability as well as safety is important, but it’s also important to understand that simplifying too much is not good either. Extreme simplification is not the way to go. Having said that, on balance we should have a reluctance to simplify. And then, when we do simplify, we need to do it very carefully and consciously.

We need to be especially tuned into any changes to systems that are under- taken after a workplace incident and its subsequent learning study. This is especially true if the incident ‘cause’ was related to the interrelationships of systems or sub-systems rather than some broken widget-type of incident. We need to watch out for putting extra barriers in place after an incident as this does not always do a very good job after incidents that were driven by system interrelationships. After all, it is important to remember that removing a component or barrier out of a complex system does not cause it to fail and adding an extra defence or barrier to a complex system does not mean it will now not fail.

Introducing improvements and changes to systems and procedures can cre- ate new ways in which people need new skills, new routines, and new activities. This can introduce new ways in which they can fail, especially until such time as the new skill, routine, or activity becomes embedded in their approaches and the way they do work. We should actively search out and destroy any ‘improvements’ that add to the already over-burdened bureaucratic systems and introduce more clutter and unnecessary system-driven requirements. We must constantly keep an eye on Work-As-Written.

Checklists as Work-As-Written also come to the fore when we are faced with complexity in the workplace. They provide an aid for judgment; a procedure to follow when the memory of the expert actor is not sufficient to handle the complexity of a task; a verification that stuff gets done in the order it needs to get done in; a set of reminders for the critical bits of the task; a buttress to the skills of the expert.

Checklists are limited and only useful for specific tasks to help experts get it right each and every time. It is important to make sure they are used sparingly and accurately. Keep them short, aiming for a maximum length of ten items.

Overall, we should also talk about the ideas of Work-As-Done, Work-As- Normal, and Work-As-Written during field leadership conversations, when talking about production and when talking about workplace incidents.

A simple way to explore the ideas behind Work-As-Done, Work-As-Normal, and Work-As-Written with people who have not seen or heard of them before is to talk through our own experiences as examples. I am making an assumption that you have all seen the following traffic control device (Figure 1).

In all the countries I have worked in, there has been a piece of legislation that tells us when the little person is red not to cross the road and when the little person is green to cross the road but endeavour to not get run over. The language varies and is usually translated into legalese, but the intent is pretty much the same. So, in this case Work-As-Written is the piece of legislation that pertains to the use of the pedestrian crossing lights.

I live in the suburb of Subiaco, which is in Perth, Australia. There is a set of pedestrian traffic control devices similar to that shown above about 200 metres from my house. Imagine that I am standing at the intersection on a cold, rainy, Sunday morning at 0700 and am watching the people as they cross the road. Am I likely to see 100% of the pedestrians crossing the road displaying 100% compliance to the procedure for crossing roads? In this case, the pedestrian lights legislation? Ah, no. I don’t think so. I am going to see a variety of behaviours ranging from those looking at their phones the whole time and just walking when they hear the Beep Beep Beep. Others will dodge traffic as they cross regardless of the colour of the lights. Some will stand there patiently until the little person goes green and then look both ways before walking and others will run if there are no cars when the little dude is red or is flashing. This is Work-As-Normal. The way I crossed the intersection as I went to set up with my little clipboard, and started watching and counting people is what would be called Work-As-Done.

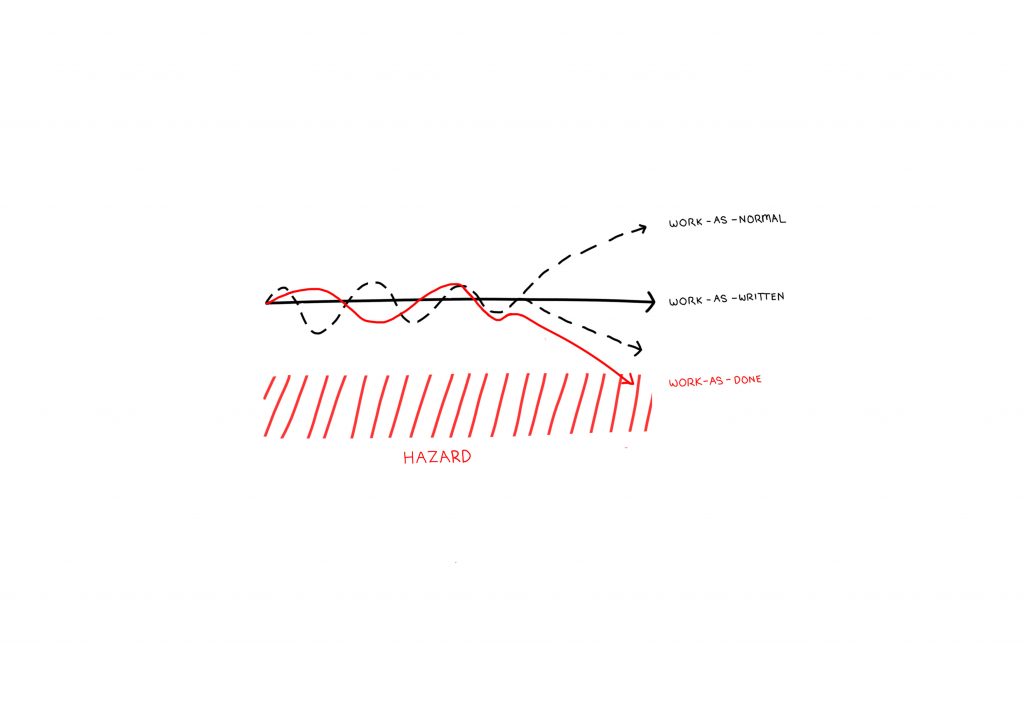

Another way to think about Work-As-Done, Work-As-Normal, and Work- As-Written is to talk through Figure 2.

The underlying hazard is just that – a hazard that is presenting various levels of risk over time. Sometimes the risk is lower and sometimes the risk is higher. Look next at the solid horizontal line marked as Work-As-Written. This is depicted as a straight line and represents the way that management has decreed that the work will be done. It could be a work instruction, procedure, set of rules, standard, Job Safety Analysis, work order, Task Hazard Analysis, Standard Work Instruction, etc. Basically anything that tells you how to do a piece of work. You will notice that at no time does the Work-As-Written line come in contact with the Hazard. This sends the message ‘Follow the rules and you will be safe’ that we often hear. You just need to look at some of the significant incidents in the past to know that following the rules blindly can be a very dangerous thing to do. I recall a few times where I have almost begun crossing pedestrian lights when the little person was green only for a driver to cross the red traffic light in front of me. Even those who simply walk when the little per- son is green are taking a considerable risk.

We know of course that not all work in our workplaces is undertaken in a manner that exactly equals the way it is written (Work-As-Written). Sometimes it is done more safely, more productively, with higher quality perhaps, and some- times it is done less safely, less productively, and with lower quality. The vast majority of the time the end result is that nothing goes wrong. This is what we call Work-As-Normal and is represented by the dashed lines. We get it right nearly all the time. In fact, whenever you go and watch people do real work, you will see a variety of behaviours; some following the rules precisely, others deviating slightly (for all sorts of good reasons), and still others deviating considerably from the Work-As-Written. Our people who do work day-in and day-out, those who face the various hazards of the workplace are nearly always controlling the risks without getting hurt. They do it not because they blindly follow the rules but because they adapt to the situations as they arise and use their skills, experiences, and knowledge to get the work done. When we look at the third wavy line, we see that the Work-As-Done line drifts away from the Work-As-Normal and Work-As-Written lines towards the hazard. This represents an incident or a near miss. This is how the work was actually done at the time of the event. It is what we would conventionally call a timeline of the incident. It could also represent the way the work was being done as we observed work during a field leadership conversation. At the end of the day, both before and after an incident, we need to be very interested and curious about how the work is being done (Work-As-Done), how others normally do the work (Work-As-Normal), and how we may think the work is done as described in our documentation (Work-As Written).

An Example

Although I started using Work-As-Done, Work-As-Normal, and Work-As- Written to help the investigation team develop a timeline and then focus on the important elements of the incident back in 2014, within a couple of years I was approached by a senior leader of a large client who mentioned that other leaders in his business were starting to use the ideas of Work-As-Done, Work- As-Normal, and Work-As-Written in their normal business conversations. They had started to formalise it during their field leadership conversations and found the ideas to be great and easy conversation starters. They could have conversations about how the task they were chatting about was being done, how other workers and their peers normally did the work, and what their thoughts were on the procedures that make up Work-As-Written. They found this a very powerful tool to help them be effective as leaders.

Key Takeaway: To get better at ‘safety’ you need to deeply understand how real work is undertaken, rather than just how you think it is being undertaken.